These blog posts follow the experiences of the BBP graduate fellows and core team as they explore our chosen rare book repositories.

The Schomburg Center in 3 Short Stories

Ivana Onubogu | Rutgers University | April 2024

These last few weeks at the Schomburg have been a whirlwind as we all continue to work on building our digital database. Three particular scenes keep arising from my memory. These are less ‘discoveries’ per se, but moments in my memory where I grew curious about the pathways for coalition between black women writers.

A Story:

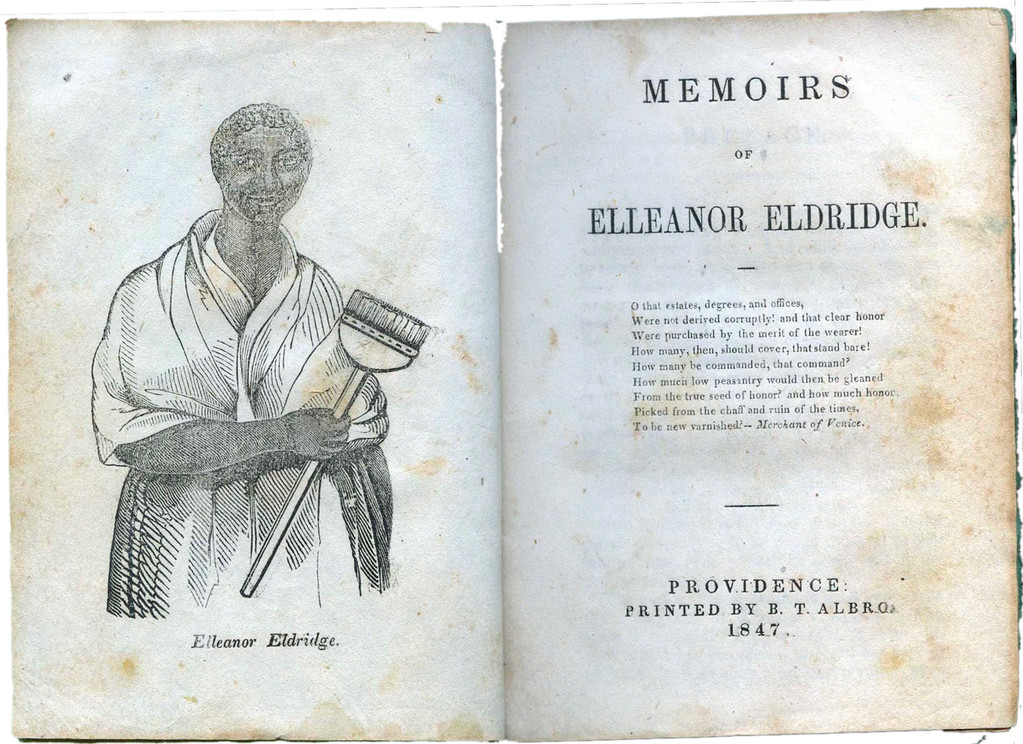

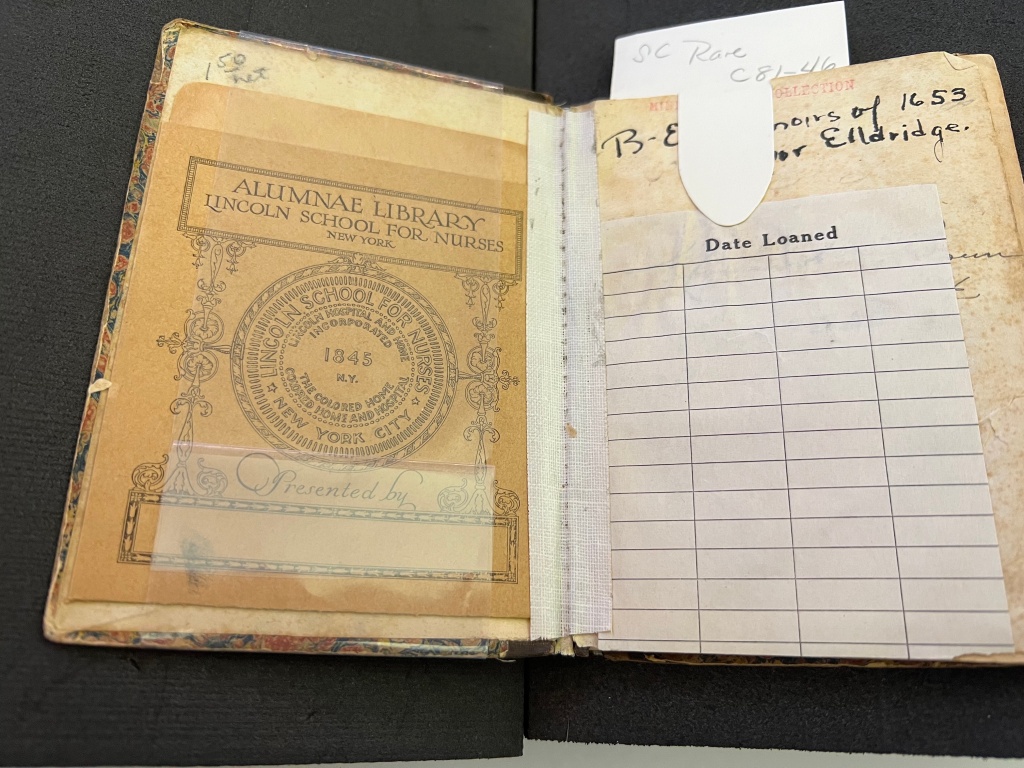

During the last two weeks, we have shifted from entering Broadside works to working on the Jean Yellin and Cynthia Bond’s bibliographic list, The Pen Is Ours: A Listing of Writings by and about African-American Women before 1910 with Secondary Bibliography to the Present. One work I found particularly interesting was not my own, but another fellow’s. She was working on Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge and, sitting across from me, was excited to show me that there were multiple editions across multiple works. We also noticed that there was a library checkout card at the front of the book stamped for the Alumnae of the Lincoln School for Nurses. After I googled it (I was curious if this was a hospital that solely trained and served the black community–it was not–), we learned that Nella Larsen was a graduate of this school. I was curious about the relationship between ‘helping professions’ and writing. For instance, how might Larsen’s formal training shaped her writing, if at all? In thinking about this relationship between ‘helping professions’ and writing, many women writers often oscillate between the two; however, this may be purely because women are often imagined as innate nurturers and encouraged to pursue such careers. By and large, I was really struck by this possible connection between Eldridge and Larsen.

Another Story:

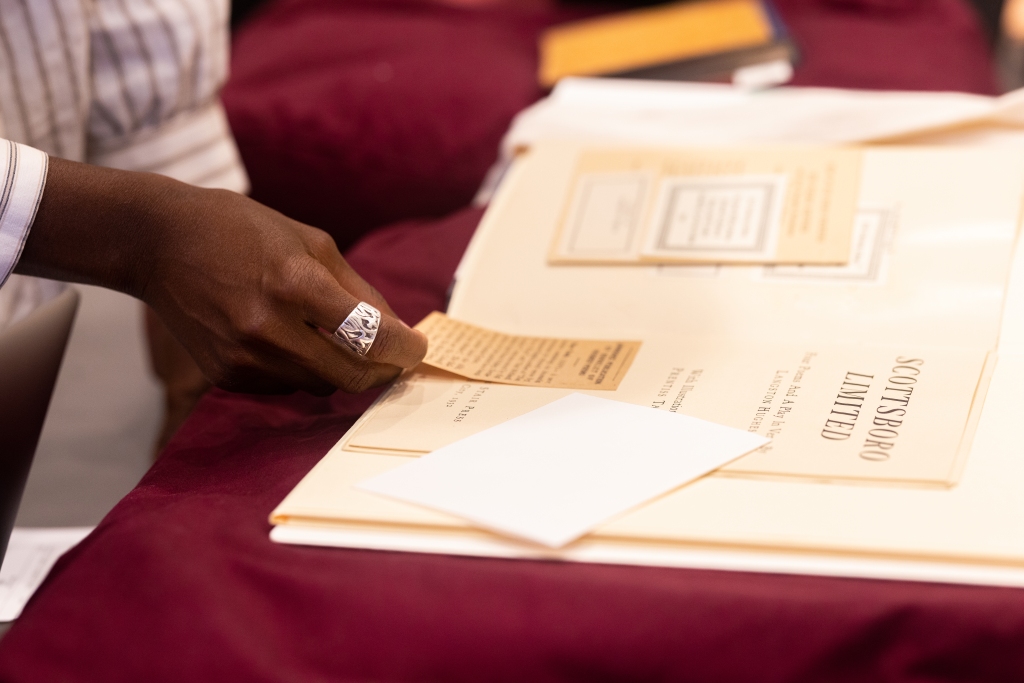

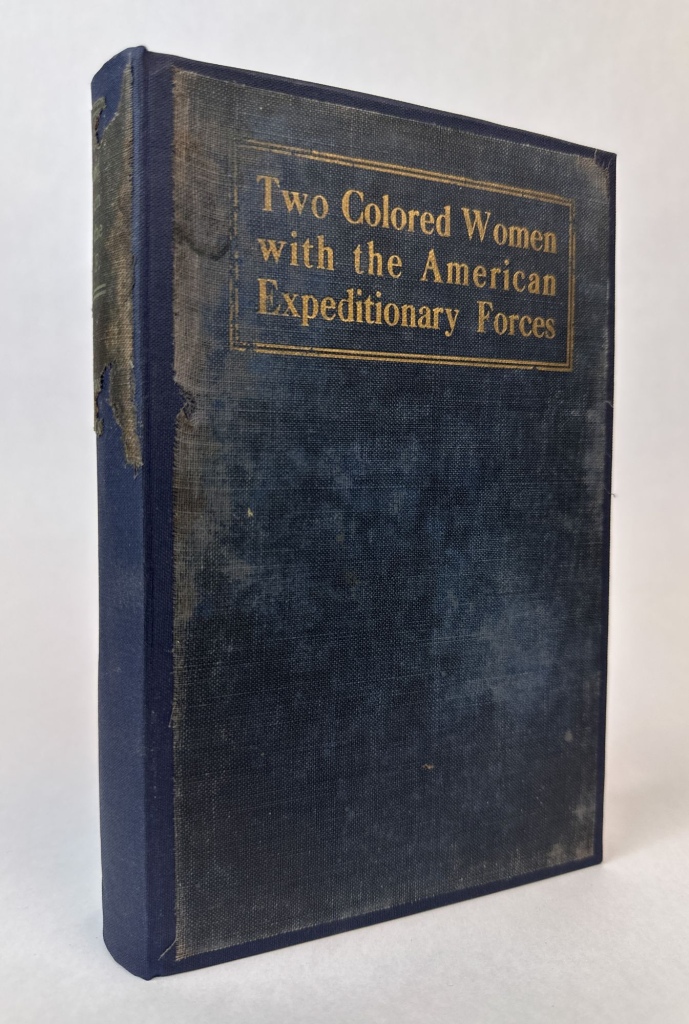

Another curious find! At the end of the last day I worked in July, I was working on Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces by Addie W. Hunton and Kathryn M. Johnson. At the front of this copy, there was a newspaper article–taped and folded to fit inside the front cover of the book–featuring a (mostly positive) book review. It was warming to see the weathered but well-preserved interjection of the newspaper clipping, like a signature of its own. It seemed to mark the interest of connecting the text with the public life of the text, of maintaining a record that is not purely the physical record substantiated by the book itself. It also could have been just a happy reminder to the authors as they celebrated their work and commemorated a positive reception.

A Sub-Story of Another Story:

The article included in the Hunton and Johnson book I’ve just mentioned was published by The Brooklyn Eagle which shares a name with the text’s publisher, Brooklyn Eagle Press. It made me curious if there was any relationship between the two. While I unfortunately could not determine what or if there was a connection between the two, this possibility laid a seed for thinking in my mind. More generally, this made me wonder about what the relationship between the book publishing press and newspapers are. I suppose they are not so far off from one another at all, but, until I saw the twin Brooklyn Eagles I never considered that related presses would use different mediums to push the same product. I look forward to learning more about this in the future!

Works Cited

Eldridge, Elleanor and Frances H. Green. Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge. Providence: B.T. Albro, 1846. Schomburg Sc-Rare B-Eldridge, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Eldridge, Elleanor and Frances H. Green. Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge. Providence: B.T. Albro, 1847. Schomburg Sc-Rare B-Eldridge, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Hunton, Addie W. Two colored women with the American Expeditionary Forces. Brooklyn, New York : Brooklyn Eagle Press, 1920. Research & Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

The Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge, or: Edition Impossible

Mitchell Edwards | Rutgers University | March 2024

This past July in the Schomburg’s special collections reading room, the other Rutgers fellows and I encountered two copies of the Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge, a work already logged in our database. Each copy bears a different publication year, identifying themselves only with a printer, B.T. Albro. Our database already featured numerous “editions” of this book—six different versions dated between 1838 and 1846—but the messy boundaries between these editions complicate that arrangement. Both volumes we examined in the reading room contained a “preface to the second edition,” despite each being counted as distinct 1846 and 1847 “editions” of the book in our database.

This was not in itself terribly surprising. Manuals of analytical and descriptive bibliography remind us insistently how common it is for books to lie about themselves or obfuscate publishing timelines—especially when it comes to their editions, as publishers or printers sometimes slap a “new edition” label onto a volume with little more than a reset title page. But these Schomburg copies of Elleanor Eldridge didn’t even go that far, only differentiating themselves by year of printing; such date discrepancies had justified the separation of all those versions as unique editions in the data model.

As we were figuring out how to describe these books, the most pressing concern was just to decide where their information should be collected: should these continue to be treated as single copies of two distinct “editions” in our system, or two printings of the same edition, differing only at the “copy” level? But a thornier set of foundational questions lay just on the other side of that choice. Deciding what we’re calling an “edition” quickly outlines the complexities of an interdisciplinary project like ours at the intersection of descriptive bibliography, print studies, and library cataloging: do we maintain a bibliographer’s suspicion of editions, counting as a new edition only a book whose type has been substantially reset? Or do we instead mirror publishers’ looser definition of “edition,” populating our database with many more edition-level items and quantifying some measure of a work’s reception as it gets reissued, with or without big changes? In the case of Elleanor Eldridge, for example, what matters more: what happened in the print shop as the book is transformed (or not) on the press across impressions, or the frequency with which its publisher decided to call readers’ attention to more recent dates of printing?

My hope is to record both what a bibliographer and the original publisher would say about this work’s production and publication history. But is there a way to navigate these questions that doesn’t sacrifice the benefits of one descriptive model over another? Our answers would have a lot of practical data implications (whether these re-printings are abstracted to the edition level or materialized at the copy level) but would also remind us that every bibliography is an argument, an articulation of values, and that it’s our (difficult) job to do as much justice to those values as we can in the descriptive choices we make.

Works Cited

Eldridge, Elleanor and Frances H. Green. Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge. Providence: B.T. Albro, 1846. Schomburg Sc-Rare B-Eldridge, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Eldridge, Elleanor and Frances H. Green. Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge. Providence: B.T. Albro, 1847. Schomburg Sc-Rare B-Eldridge, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Reflection on the first BBP Wikidata Edit-a-thon

Jeania Ree Moore | Yale University | February 2024

Fig. 1 Event Poster for Black Bibliography Project’s January 2024 Wikidata Edit-A-Thon

Last week we had our first BBP Wikidata Edit-a-thon in the Digital Humanities Lab at Sterling Memorial Library. I went in not knowing what to expect. Having been introduced to wiki building and interfacing solely from our BBP website training last summer, I was curious about how this differed from and connected to what we do on a day-to-day basis. I also, admittedly, wondered how much I would be able to actually learn and implement in the span of an afternoon workshop.

When I arrived at the DH Lab, the first thing I noticed was the set-up. Multiple chairs were placed at the tables, which formed a loose horseshoe shape facing each other and the screen. And what’s more—and was a welcome sight on a Monday afternoon—a room stocked with coffee, tea, and snacks was provided for us just off to the side.

The second thing I noticed was who else was arriving to participate. A mix of students and what appeared to be library staff soon filled the chairs around me. When I asked my desk partner where they hailed from in the university, they responded that they were a data librarian in the medical school who had learned about the event from Yale University Library’s DEIA email uplifting events related to the university’s weeks-long MLK Jr. Day commemoration. By the time the workshop started, the room was a buzzing cross-section of various parts of the university that don’t normally interact, especially on research projects working in a manner where everyone—undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, staff—is doing the same thing, rather than separate, specialized, and, often, hierarchized tasks.

As explained in the opening orientation, our task for the afternoon was creating the background data that populates pages in Wikidata, a platform used by Wikipedia as well as Google (in those nifty data sidebars). Whereas our day-to-day tasks with the BBP are bibliographical, focused on creating bibliographic data supporting texts in the BBP database, our work that day in the Wikidata Edit-a-thon was biographical.

We were creating and filling in data points for people that did not yet exist in the massive Wikidata database, or who existed but whose record lacked information. These people are writers, scholars, authors, activists, printers, publishers, newspaper editors, and more—all connected in some way with the Black texts that are the focus of the BBP.

Over the course of the event, I realized that the learning curve was way less steep than I anticipated. And I discovered that our learning not only built on itself, but also built on and encouraged the nascent community in the room. In its accessibility, its critical engagement, and its communal setting, the entire event reinscribed the ethics and collaborative infrastructure of the BBP in new ways.

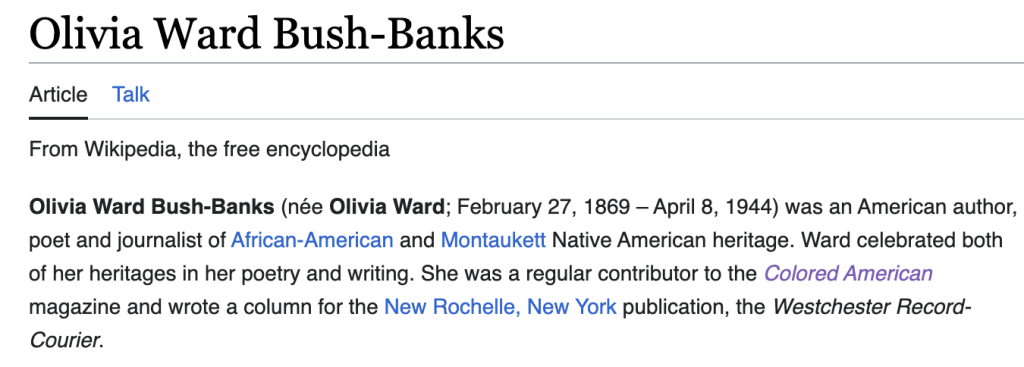

In terms of access, the Wikidata Edit-a-thon was much more open physically and technically (“know-how”) than most archivally-related research I have encountered. Anyone could just wander in and join us for a couple hours or thirty minutes, and see the impact they were making. It’s not often that a highly theoretical, conceptually sophisticated research project is so on-the-ground and open to people at all stages to contribute, make a difference, and see that difference in real time. We could easily create a person and add to the vast knowledge enterprise of Wikidata, redressing gaps and adding details that facilitated other connections. For instance, in the process of creating a data point for historian Bernice Forrest, I also corrected the record for the writer whose works she edited, her great-grandmother, nineteenth-century poet Olivia Ward Bush-Banks.

Fig. 2 Image of Olivia Ward Bush-Banks’ Wikipedia Page

I edited Bush-Banks’ Wikidata page to more accurately record her ethnic heritage as not just African American but also Indigenous American and specifically Montaukett—details that were missing in the prior entry and a fact that matters, especially given that Bush-Banks served as historian for the Montaukett tribe. Previously, had someone done a search in Wikipedia for Montaukett individuals or writers, neither Bush-Banks nor Forrest would have appeared; now, they both will. It’s something small that yet feels significant, in its personal meaning and connection. (If you’re interested, you can read more about Forrest and Bush-Banks here).

The reduced barriers to participation did not mean ours was not a critical task. As participants, we found ourselves in frequent conversation with our desk partners and others around the room, raising questions and crowdsourcing answers on how to address tough situations of categorization and data description. It’s one thing to read about and analyze critiques of the politics of cataloguing, archival data, and historical language; it’s another thing to face the challenge and try to tackle the task of recuperating knowledge and intervening in historical memory to populate a database. One document whose related biographical data I wrestled with inputting was a slave narrative that was also a gallows statement from four enslaved people who were executed for homicides in Missouri. How do we list these individuals? What biographical data is knowable about them? How do we record and wrestle with the limits of knowing, related to this document? It was good to be in community in that work of trying to figure out answers to these questions.

Fig. 3 Scanned Title Page of Trials and Confessions of Madison Henderson, alias Blanchard, Alfred Amos Warrick, James W. Seward, and Charles Brown, Murderers of Jesse Baker and Jacob Weaver, as Given by Themselves; and a Likeness of Each, Taken in Jail Shortly after Their Arrest

Lastly, and relatedly, the nature of the space and work drove home the collective responsibility of the task of knowledge creation. This struck me as both an epistemological meta-commentary on the BBP itself and an actual reality shaping us in that workshop. The physical set-up of the room encouraged conviviality, conversation, movement, and exchange—so different from most archive reading room experiences I have had where the spatial and acoustic arrangement seems to emphasize that the work of knowing is silent, solitary, and absolutely no food allowed! Humor aside, the practical nature of this collective responsibility was one of the biggest takeaways from the Wikidata Edit-a-thon. If we weren’t already, that day we became Wikidata contributors! As someone who had always wondered about but been more than a little intimidated by the prospect of becoming a Wikipedia contributor, I found this super cool. And it was even cooler to leave with confidence in a role that had mystified me.

Empowerment from community is what the BBP is about: bringing to light the vast community of actors in relation to Black books and texts. Our work in the Wikidata Edit-a-thon was a different but no less impactful angle on that same yield.

Works Cited

Henderson, Madison, et al. Confessions of Madison Henderson, Alias Blanchard, Alfred Amos Warrick, James W. Seward, and Charles Brown, Murderers of Jesse Baker and Jacob Weaver, As Given by Themselves: and a Likeness of Each, Taken In Jail Shortly After Their Arrest. Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture, 1790-1920. [Place of publication not identified]: [publisher not identified], 1841

Scott, Ivy. “Roots Reconnected.” Brown Alumni Magazine, 21 Jun. 2022, http://www.brownalumnimagazine.com/articles/2022-06-21/roots-reconnected. Accessed 22 Jan. 2024.

Wikipedia, Olivia Ward Bush-Banks. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olivia_Ward_Bush-Banks

The Stories Books Tell

Jorden Sanders| Rutgers University | December 2023

How often do you think about the lives who have touched a book? We’re accustomed to thinking about the lives that books touch—the way their content moves hearts and changes minds unbounded by time—but do we consider how we interact with the material object itself? How many hands have held its weight or flipped through its pages? In a world where books are often imagined to be products of machine labor, purchased new, or read in digital formats, it is easy for the histories of the book itself to slip our minds.

Doing descriptive bibliography in the Rare Book Room of the Schomburg reminded me in very tangible ways that books have lives, and the stories they tell actively shift how one approaches the words inside.

My reminder began with the binding.

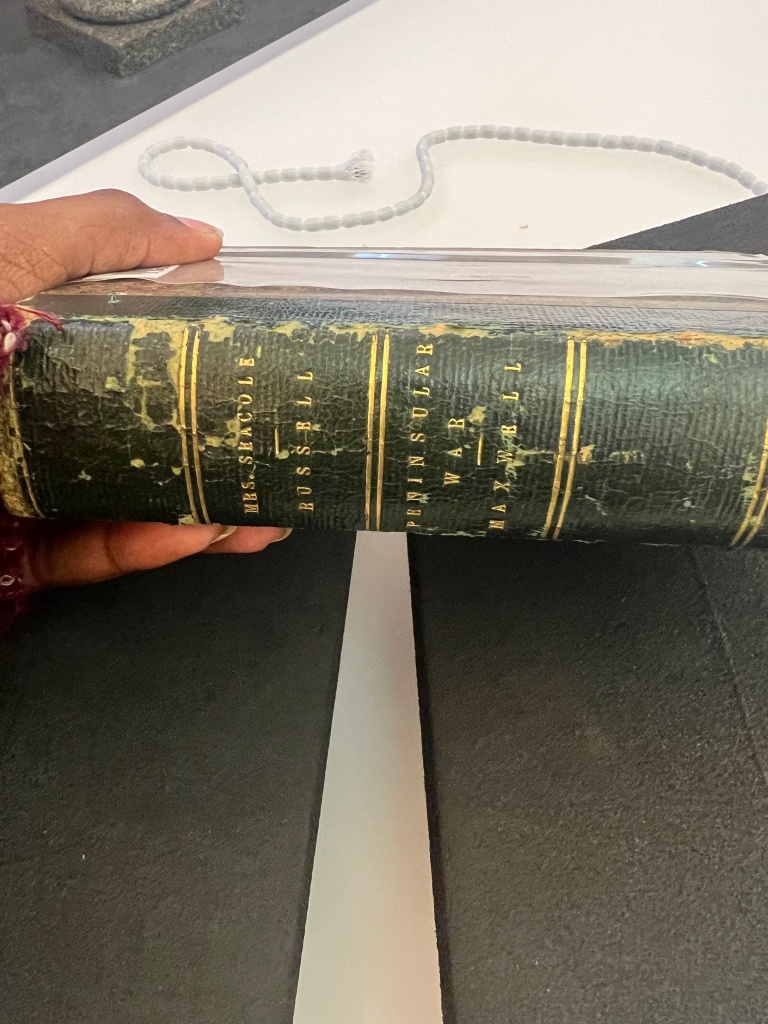

Prepared to encounter a copy of The Wonderful Adventures of Mary Seacole, I was surprised to find the story bound with W.H. Maxwell’s Stories of the Peninsular; or, Peninsular Sketches (See Figure 1). It was not my first time encountering texts that had been bound together, but other texts I had seen were intentionally printed together in order to create a thematic reading experience. The title pages of these two texts show that the individual works were published in two separate shops on the same street. Because these texts were originally published and printed separately, the choice to bind these texts together rests with a reader—one who saw the value of packaging adventures together that lived experiences might have kept separate.

While a book like this told me the story of one reader’s trip down Paternoster row, other texts reminded me that each book actually tells the stories of many.

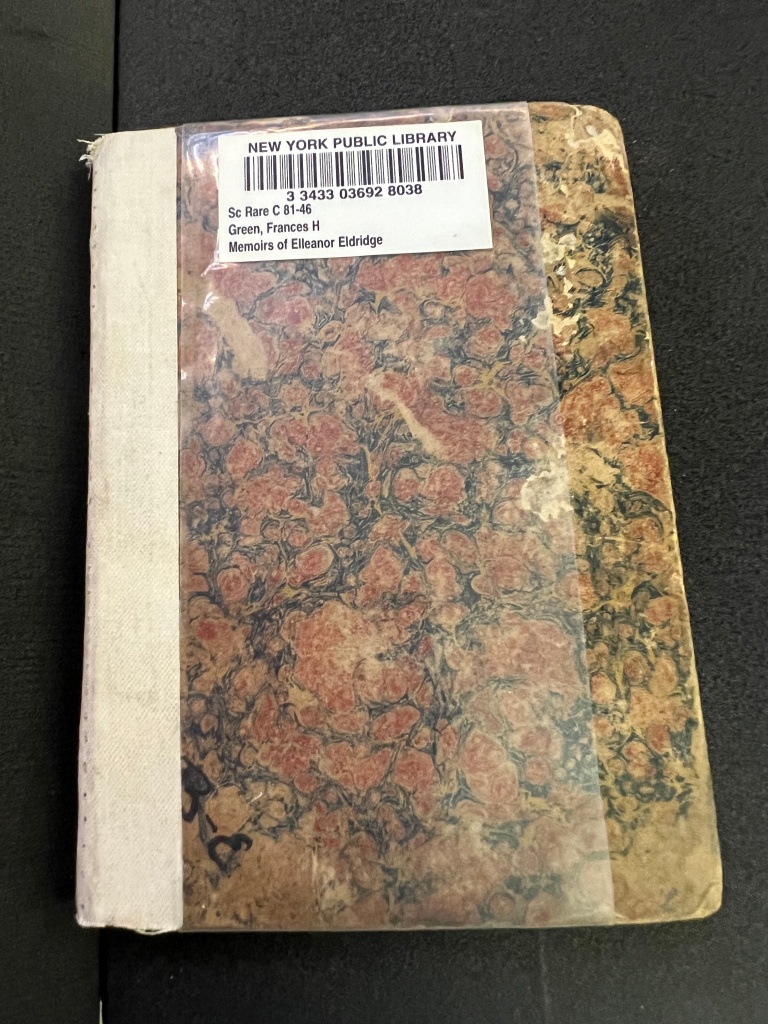

This was the case when I opened the Schomburg’s copy of Memoirs of Eleanor Eldridge’s 1841 edition (See Figure 2). Rebound in a beautiful floral cover, the fraying edges and taped spine suggest that the book has been handled often. Attached to the front endpaper is a manila envelope stamped with the seal of the Lincoln School for Nurses in New York’s Alumnae Library (See Figure 3). Its placement across from a blank leasing log confirmed my suspicion that the envelope once housed the book’s borrowing history. According to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture’s records, The Lincoln School for Nurses certified 1,864 women between 1900 and 1961. One of which was Nella Larsen as part of the 1915 class (Hutchinson 88).

There is so much to learn from exploring who has handled the books we cherish. Who has held its weight and perused its pages? What does it mean for books to move among spaces of Black learning—particularly spaces dedicated for Black women? Now that I have handled these books as part of the Schomburg’s reading community, I can’t help but wonder what story the book will tell.

Work Cited

“Biographical/Historical Information,” Lincoln School for Nurses collection, Sc MG 248, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts.

Hutchinson, George. “A Black Woman in White: New York, 1912-15.” In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line, Belknap Press, 2006, pp. 75-89.

“Lincoln School for Nurses in New York’s Alumnae Library Seal, ” Memoirs of Eleanor Eldridge, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Maxwell, W. H. Stories of the Peninsular War; or Peninsular Sketches. Charles H. Clarke, Copyright Edition, [year unknown].

“Memoirs of Eleanor Eldridge (1841) cover,” Memoirs of Eleanor Eldridge, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Seacole, Mary. Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands. Edited by W.J.S., James Blackwood, 1857.

“Seacole-Maxwell Spine,” The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands bound with Stories of the Peninsular War; or Peninsular Sketches, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Can I Take This Home?

Kristine Guillaume | November 2023

I’ve been redecorating my apartment lately — or rather, just decorating. Since moving to New Haven last year, I’ve learned that the process of setting up a space so that it feels something like home can take a long time. It’s been wonderful to have some time this summer to finally hang art on my walls and make my apartment feel more lived in. Perhaps because I’ve been in this mindset of looking for things — posters, prints, plants — that might accentuate my space, I’ve been thinking a lot about illustration, aesthetics, and presentation while engaging with the Broadside Press’ poetry published in the broadside format. Many times, I’ve found myself thinking about how I’d like to have a broadside framed and hung up on the wall, either in my own home or elsewhere.

A few years ago, my friend framed a printout of Robert Hayden’s “Frederick Douglass” and gifted it to me, and it’s one of my most treasured items in my room. Looking at the broadsides, I’ve often remembered how special it is for me to have that poem in my home, and I find myself having the intrusive thought:

“Can I take this home?”

(Of course, only kidding.)

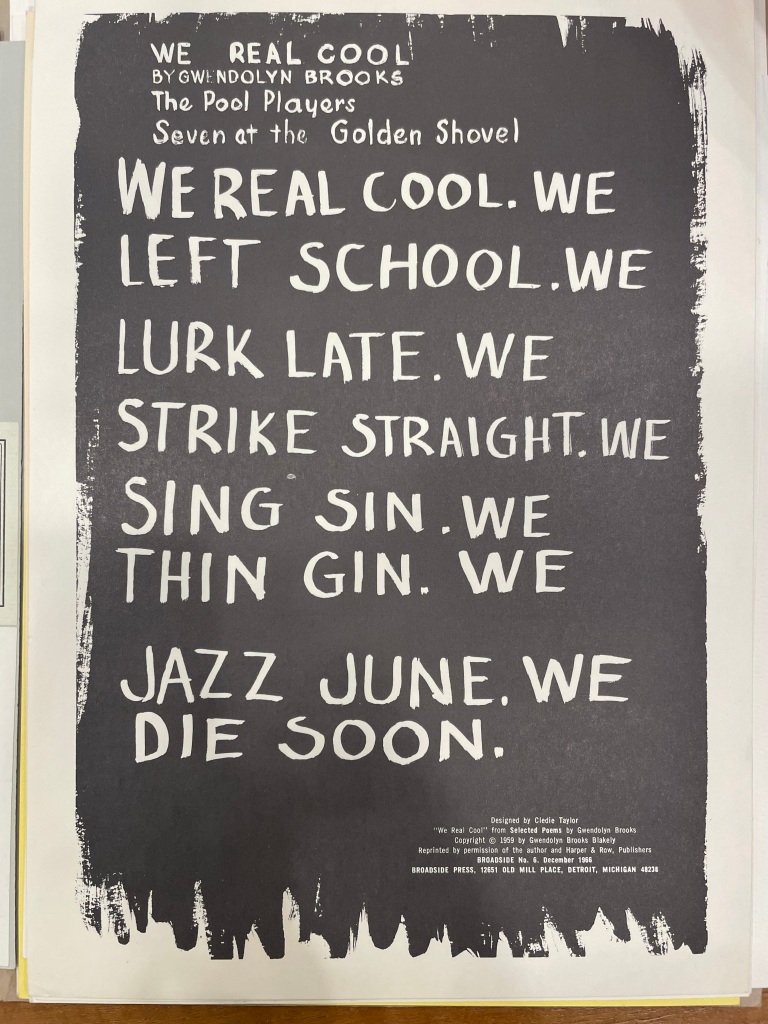

I thought about what it might mean to have one of the broadsides hanging in my space when I came across the broadside edition of Gwendolyn Brooks’ famous poem “We Real Cool.”

James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. [1]

The aspect of broadsides being shared or placed in public view is particularly important because many of these broadsides were printed in limited quantities, oftentimes 300-500 copies. This made me think about a presentation that Amanda Awanjo, the BBP’s project manager, gave during our summer workshop, in which she spoke about how Brownies’ Books were shared amongst children who read them. There is a sociality that we can imagine being practiced through the communal use of these books, and I find that to be a really important element of how we think about Black print culture. This sociality calls to mind the work of artist and book publisher Tia Blassingame, whose printmaking work actively seeks to foster a dialogue about contemporary and historical racism in the United States, especially examining Rhode Island’s role in the slave trade.[2] Blassingame, who argues that printed word carries an “authority,” uses the tactility of letter press text and printmaking to bring people into a conversation about this history. The material text, for Blassingame, provides an entry point, especially as she views people as “users” of her books.

I’m interested in the notion of “users” here. What does it mean to produce a text to be used? Blassingame’s books are tactile conversation starters in a way that might be analogous to the broadsides. The broadsides play with material text elements such as color, illustrations, and typeface to convey the poem. While some are big and bold like Brooks’ “We Real Cool,” others have illustrations such as the 1970 broadside edition of Etheridge Knight’s “For Black Poets Who Think of Suicide” and others are quite plain. It is interesting to be engaging with the broadsides in the archives rather than to be seeing them in public space, but seeing so many different variations prompts a lot of questions for me about how people might be reading, experiencing, and discussing these works together.

Works Cited:

[1] Gwendolyn Brooks, We Real Cool, 1966 Broadside edition (Detroit, MI: Broadside Press, 1966), Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

[2] Tia Blassingame: Combating Racism through Letter Press Printing (Design Indaba, 2015)

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.