Finding Mirrors in the Archive: Richard Allen Homes & Geographies of Black Life

Tyler Isaiah Campbell | Yale University | April 2025

This past week, I dove into the depths of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a place steeped in the essence of Black legacy. I’ve been here before—countless events, exhibitions. But this time, it was different. I wasn’t just passing through; I was reaching into the roots of history, digging through the stacks, feeling the weight of the scholars who walked these halls before me. Their spirit lingered, infused in the air, reminding me that I’m part of this great, unending struggle, this continuum of Black thought and resistance.

Last Friday, on the very day we celebrated the 100th birthday of James Baldwin, I stumbled upon a book with a title that made me laugh out loud: Who Was Richard Allen and What Did He Do? It sounded almost comical, invoking memories of The Richard Allen Homes, a housing project back in North Philly where I played as a kid with friends. The echoes of 4th of July block parties, the sizzling fish fry’s, the thrill of playing manhunt at dusk, ducking between parked cars to avoid being caught, and those hot summer days spent playing “curb ball” in the alley behind 10th Street—they all flooded back. But it never crossed my young mind—much less as the book’s title asks—who this Richard Allen was. Some grumpy old man used to yell at us to keep it down, and we kids would whisper that he was “the Richard Allen.” No one bothered to check the facts; we were too busy living.

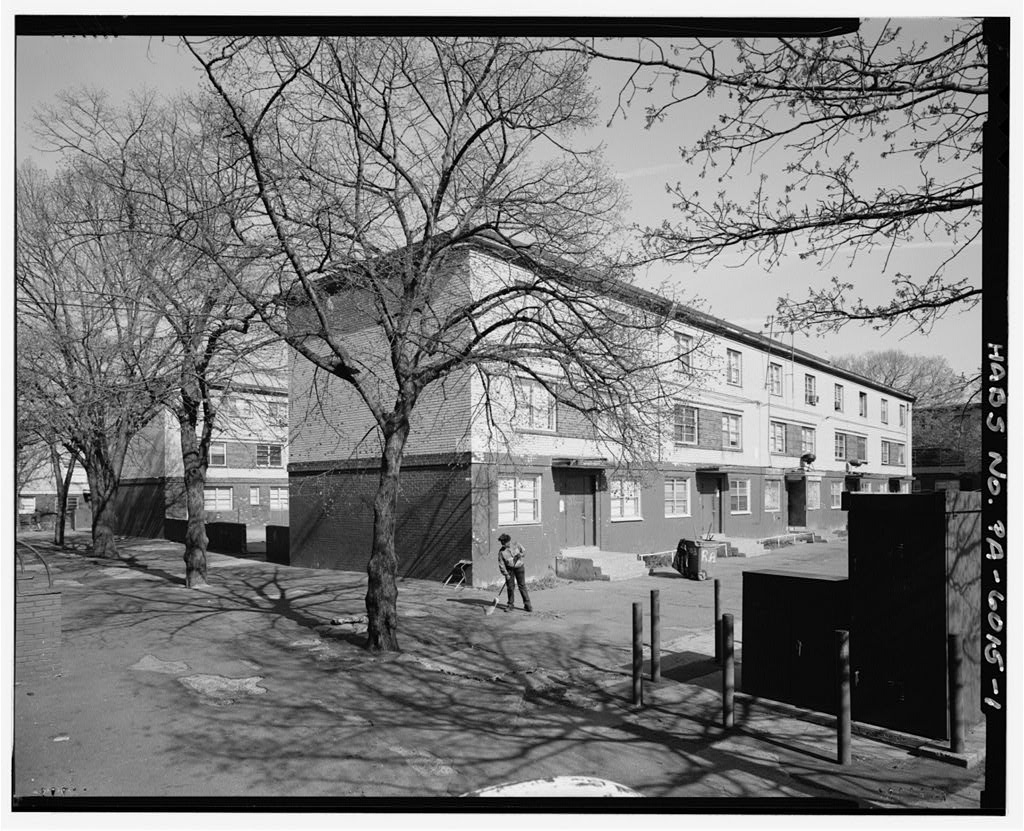

Flipping through the pages, I discovered Richard Allen—the founder of Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, a titan in Black Methodism in this land of contradictions. His leadership was more than just a title; it was a beacon, a clarion call for Black people fighting for their place in a world that often cast them aside. So, in 1941, they named the city’s first low-rent housing project after him. A $7.4 million dream built on Bauhaus principles, it transformed a broken landscape into something new, something that aimed to reflect the hopes of a people yearning for dignity and progress.

But here’s the truth: Richard Allen Homes aren’t the symbol of community and Black prosperity they were supposed to be. Even back when I was a kid, it wore the badge of violence, a reflection of deeper scars that run through our communities. Violence isn’t just an act; it’s a symptom of a system that’s failed us time and time again. The vision for Richard Allen Homes stands in stark contrast to the reality today, a painful reminder of the ongoing battles we face as Black folks trying to survive historical injustices.

And I can’t help but wonder: what role our work plays in this relentless fight for better lives, in redefining these spaces, and reshaping our communities. How do we ensure that our efforts don’t just scratch the surface but dig deep, fostering long-term, sustainable progress and equity? We must remember that we’re building futures, not just addressing immediate needs; the legacy we inherit demands more from us. It calls us to engage with our landscapes, spatializing our narratives to craft a vision that honors our complexity and richness. This is a fight that requires us to confront the realities of our existence, to transcend mere survival and cultivate a future where Black lives truly matter. We must fight fiercely with our pens, our voices, and our very beings for a world that acknowledges and celebrates the full spectrum of Black life, transforming our geographies into realms of possibility.

Work Cited

Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator. Richard Allen Homes, Bounded by Poplar & Ninth Streets, Fairmount Avenue & Twelfth Street, Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, PA. Documentation Compiled After. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/pa2961/>.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.