Instance of: [Black] [Feminists] [at Work]

Sydney Smith & Brittany Marshall | Rutgers University | February 2025

*the following is a selected transcript from a conversation between two Black feminist bibliographers. Click here to read the full conversation.*

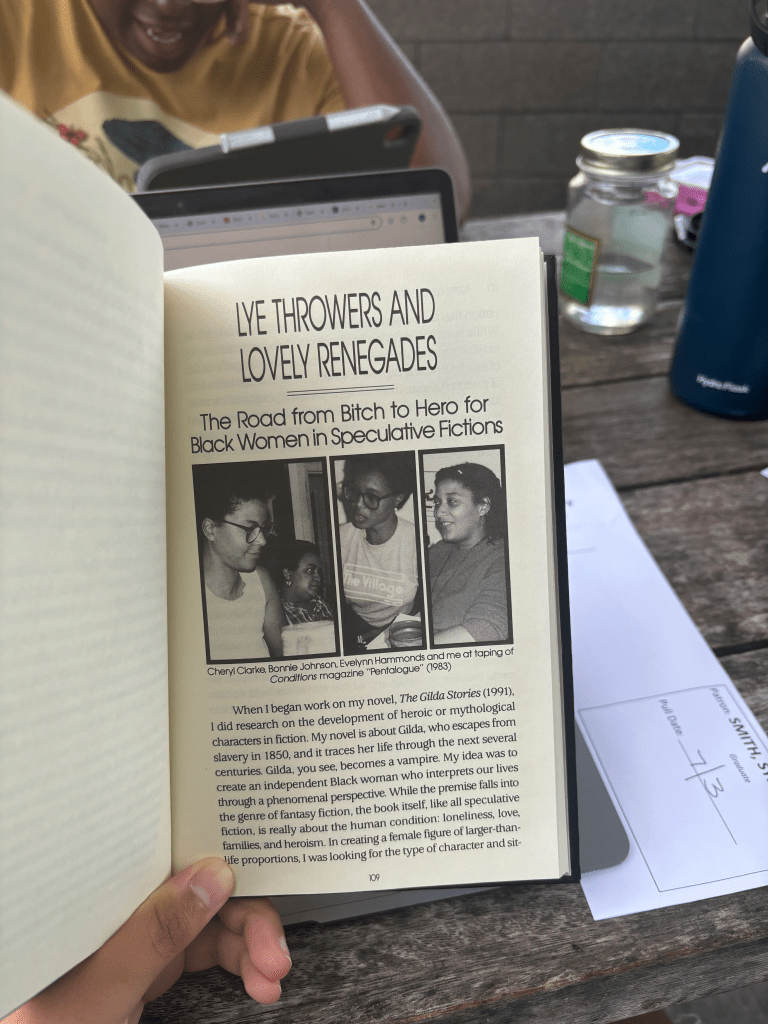

This past August, we got together via Zoom to have a recorded conversation about the intersection between Black feminist theory/praxis and descriptive bibliography. Some of the topics covered include: tenets of Black feminist theory and their relationship to technical aspects of bibliographic data entry, public facing scholarship, and the teachers who got us here. We enabled captions during our Zoom call and used the provided transcript to edit and condense the conversation. Therefore, readers won’t get a sense of other dynamics of the conversation such as body language and validating remarks like ‘hmmm’ or ‘yeah.’ In Homegirls, Barbara Smith expressed a desire to recreate the laughter she and Cenen shared as “it was the laughter of recognition.” We would also add that head tilts, raised eyebrows, and pursued lips are facial expressions of recognition as well. Unfortunately, we couldn’t recreate them here. Nonetheless, this conversation was done in the spirit of two other conversations[1] by some of our favorite and guiding Black feminists: Barbara Smith, Cheryl Clarke, and Jewelle Gomez.

How Did We Get Here?

Sydney: I feel like it would be nice to start with something about why we even felt the need to bring in Black feminism into the conversation about data entry, descriptive bibliography, and the Black Bibliography Project.

Brittany: Well, it started with trying to figure out who Bonnie Johnson was. Who is this woman? How do we find her? Because you had to put her in the data model, but we needed to confirm her identity so to speak. And you and I both study Black feminist thought so when we come across somebody we don’t know there’s instantly a question of Well why don’t we know them? How can we get to know them? And doing descriptive bibliography requires that you account for people. And I feel like that’s also a part of Black feminism: it’s about collectivity and community. They’re always bringing each other in. They branch out and bring in. They branch out and bring in. So, in trying to find Bonnie Johnson, we were both hunched over our laptops trying to branch out so we could bring her into the database.

S: I was just feeling like Black feminist writing was there, but it wasn’t something that was explicitly named. Like at the data entry level, there is no Black feminist list. You can’t trace the history of 20th century, especially late 20th century, Black writing, and not talk about the body of work produced by Black feminists. The goal of the project is to trace genealogy of Black writing throughout centuries. And Black feminism is really concerned with genealogies and paying homage to a specific kind of tradition.

B: You know something that’s always on my mind with this kind of work is that I’ll come across a name, and I automatically assume they’re a feminist. And I ask myself: Should I assume that? And I think maybe it’s fine to do so. Because so much of their work and how they come together talking to each other. It’s like, well, this [feminism and women’s empowerment] is the thing that has brought them together. Yes, they’re friends, but also co-conspirators and colleagues, you know? You know there’s this book–. I’m sure you know it, cause you’re a historian, but it’s called A Black Women’s History of the United States[2], and so a lot of times when I’m doing this work–especially stuff off the Black Indie list–I’m like, what would a Black woman’s history of the book look like?

Tenets of Black Feminism Meet Descriptive Bibliography

S: I feel like this would be a good transition to the first question: What makes a Black feminist text? What are those principals and tenants?

B: That’s a hard question.

S: One is the practice of naming. Naming who are your influences in terms of how you understand yourself, how you understand race and gender positionality, and how you move through the world. Part of it almost feels too obvious to name, but I do think that it differentiates Black feminist writing– the way that you acknowledge Black women’s intellectual production, especially when it falls outside of the bounds of academia. People talk about family members and ancestors shaping the way they think, what they’re writing about, and how they understand themselves. In the anthology Home Girls, Barbara Smith’s essay “Home” talks about how her first lessons of Black feminism were from the women in her life: her sister, her mother, her grandmother, and her great aunt.[3] Another example is Assata Shakur’s autobiography. It’s a political autobiography, because she’s mapping how racial capitalism is the governing logic of the United States, but it’s such a thoughtful meditation on her relationships with the women in her life, especially her daughter.

B: I like that you used the word meditation because I feel like it’s always a meditation on how you know what you know. Because you got it from somebody! Maybe you call it women’s intuition or a gut feeling. But even that has been nurtured in you, you know? Other women have been around you and affirmed you enough and validated you enough to even have that experience. So questions like Who gave it to you? Who helped you? are so central. Naming your people and all that demonstrates that they know how to give credit. And not only that they know how to do it, but that they firmly believe in it! You know I grew up in the South (Louisiana) and I was raised by my grandparents and they are just as Southern Black and Country as you can get. And growing up, going around other people it was always an icebreaker of Who are you? Who yo’ people is? Who yo’ mama? Who yo’ grandma? Always wanting to know the women I’m related to.

S: Who do you bring with you?

B: Exactly.

Click here to read the full conversation.

[1] The first conversation is a dialogue in Conditions: Nine (1983). The second conversation is between Barbara Smith and Cenen in Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983)

[2] This a book by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross, Penguin Random House (2021)

[3] Barbara Smith, “Home” in Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, ed. Barbara Smith (Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983).

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.