The Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge, or: Edition Impossible

Mitchell Edwards | Rutgers University | March 2024

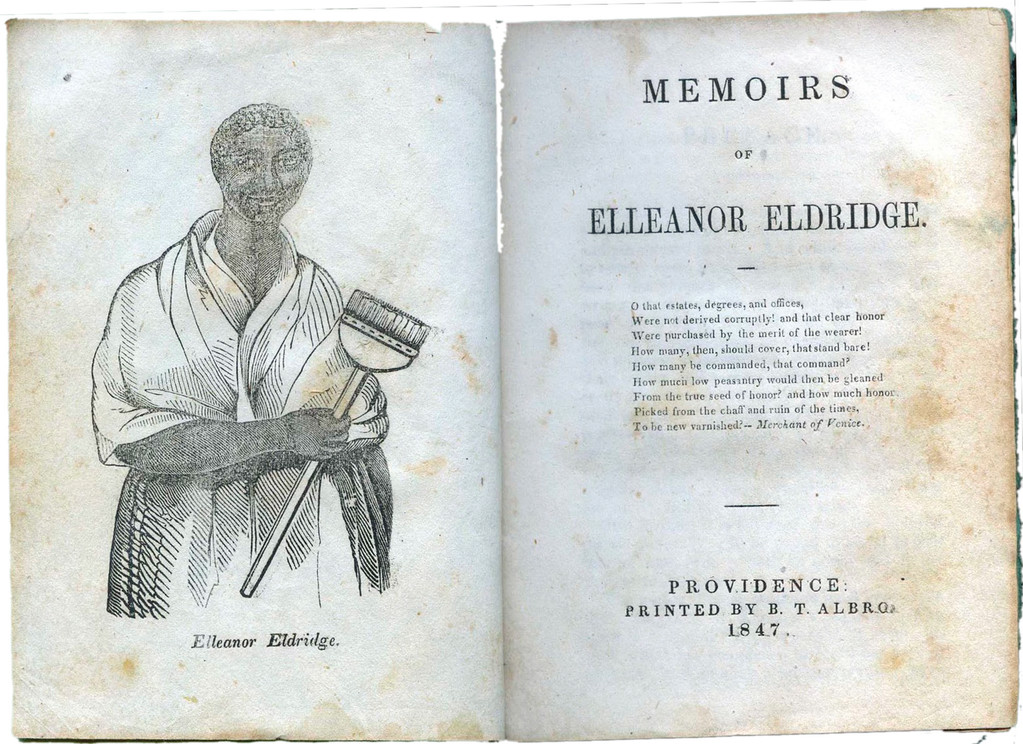

This past July in the Schomburg’s special collections reading room, the other Rutgers fellows and I encountered two copies of the Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge, a work already logged in our database. Each copy bears a different publication year, identifying themselves only with a printer, B.T. Albro. Our database already featured numerous “editions” of this book—six different versions dated between 1838 and 1846—but the messy boundaries between these editions complicate that arrangement. Both volumes we examined in the reading room contained a “preface to the second edition,” despite each being counted as distinct 1846 and 1847 “editions” of the book in our database.

This was not in itself terribly surprising. Manuals of analytical and descriptive bibliography remind us insistently how common it is for books to lie about themselves or obfuscate publishing timelines—especially when it comes to their editions, as publishers or printers sometimes slap a “new edition” label onto a volume with little more than a reset title page. But these Schomburg copies of Elleanor Eldridge didn’t even go that far, only differentiating themselves by year of printing; such date discrepancies had justified the separation of all those versions as unique editions in the data model.

As we were figuring out how to describe these books, the most pressing concern was just to decide where their information should be collected: should these continue to be treated as single copies of two distinct “editions” in our system, or two printings of the same edition, differing only at the “copy” level? But a thornier set of foundational questions lay just on the other side of that choice. Deciding what we’re calling an “edition” quickly outlines the complexities of an interdisciplinary project like ours at the intersection of descriptive bibliography, print studies, and library cataloging: do we maintain a bibliographer’s suspicion of editions, counting as a new edition only a book whose type has been substantially reset? Or do we instead mirror publishers’ looser definition of “edition,” populating our database with many more edition-level items and quantifying some measure of a work’s reception as it gets reissued, with or without big changes? In the case of Elleanor Eldridge, for example, what matters more: what happened in the print shop as the book is transformed (or not) on the press across impressions, or the frequency with which its publisher decided to call readers’ attention to more recent dates of printing?

My hope is to record both what a bibliographer and the original publisher would say about this work’s production and publication history. But is there a way to navigate these questions that doesn’t sacrifice the benefits of one descriptive model over another? Our answers would have a lot of practical data implications (whether these re-printings are abstracted to the edition level or materialized at the copy level) but would also remind us that every bibliography is an argument, an articulation of values, and that it’s our (difficult) job to do as much justice to those values as we can in the descriptive choices we make.

Works Cited

Eldridge, Elleanor and Frances H. Green. Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge. Providence: B.T. Albro, 1846. Schomburg Sc-Rare B-Eldridge, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

Eldridge, Elleanor and Frances H. Green. Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge. Providence: B.T. Albro, 1847. Schomburg Sc-Rare B-Eldridge, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.